The video blogger had visited Dongji Village, in eastern China, to find a man known for raising eight children despite deep poverty. The man had become a favorite interview subject for influencers looking to attract donations and clicks.

But that day, one of the children led the blogger to someone not featured in many other videos: the child’s mother.

She stood in a doorless shack in the family’s courtyard, on a strip of dirt floor between a bed and a brick wall. She wore a thin sweater despite the January cold. When the blogger asked if she could understand him, she shook her head. A chain around her neck shackled her to the wall.

The video quickly spread online, and immediately, Chinese commenters wondered whether the woman had been sold to the man in Dongji and forced to have his children — a kind of trafficking that is a longstanding problem in China’s countryside. They demanded the government intervene.

Instead, local officials issued a short statement brushing off the concerns: The woman was legally married to the man and had not been trafficked. She was chained up because she was mentally ill and sometimes hit people.

Public outrage only grew. People wrote blog posts demanding to know why women could be treated like animals. Others printed fliers or visited the village to investigate for themselves. This was about more than trafficking, people said. It was another reason many young women were reluctant to get married or have children, because the government treated marriage as a license to abuse.

The outcry rippled nationwide for weeks. Many observers called it the biggest moment for women’s rights in recent Chinese history. The Chinese Communist Party sees popular discontent as a challenge to its authority, but this was so intense that it seemed even the party would struggle to quash it.

And yet, it did.

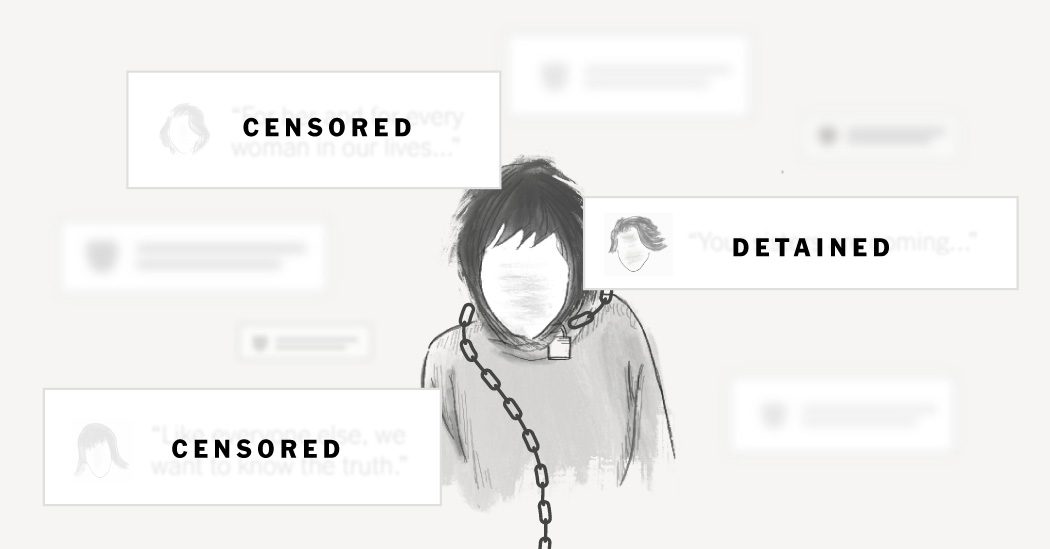

To find out how, I tried to track what happened to the chained woman and those who spoke out for her. I found an expansive web of intimidation at home and abroad, involving mass surveillance, censorship and detentions — a campaign that continues to this day.

The clampdown shows how rattled the authorities are by a growing movement demanding improvements to the role of women in Chinese society. Though the party says it supports gender equality, under China’s leader, Xi Jinping, the government has described motherhood as a patriotic duty, jailed women’s rights activists and censored calls for tougher laws to protect women from mistreatment.

Yet even as the crackdown forced women to hide their anger, it did not extinguish it. In secret, a new generation of activists has emerged, more determined than ever to continue fighting.

Who Is the Chained Woman?

At first sight, Dongji looks like any other village in China’s vast countryside. Two hours from the nearest city, it sits among sprawling wheat and rice fields in Jiangsu Province, half empty, most residents long departed to look for better lives elsewhere.

But when a colleague and I visited recently, one house, with faded maroon double doors, appeared to be guarded by two men. A surveillance camera on a nearby pole pointed directly at the entrance.

This was the street where the chained woman had lived.

Officially, there was little reason that her house should still be under watch, since in the government’s telling, the case had been resolved.

After widespread outrage over the government’s initial statement, in January 2022, officials promised a new investigation. Over the next month, four government offices released statements that at points conflicted with each other — offering different dates for when she was first chained, for example, or alternately suggesting that she had been homeless or gotten lost before arriving in Dongji. Finally, under intense public pressure, provincial officials in late February that year issued what they said was the definitive account.

According to that report, the woman was named Xiaohuamei, or “Little Flower Plum.” (The government did not specify whether that was a nickname or a legal name.) She was born in Yagu, an impoverished village in Yunnan Province, in China’s southwest.

As a teenager, she at times spoke or behaved in ways that were “abnormal,” the report said, and in 1998, when she was around 20, a fellow villager promised to help her seek treatment. Instead, that villager sold her for about $700.

Trafficking women has been a big business in China for decades. A longstanding cultural preference for boys, exacerbated by the one-child policy, created a surplus of tens of millions of men, many of whom could not find wives. Poor, rural men in eastern China began buying women from the country’s even poorer western regions.

Xiaohuamei was sold three times, finally to a man in Dongji — more than 2,000 miles from her hometown — who wanted a wife for his son, Dong Zhimin, the government said.

Over the next 20 years, she gave birth to eight children, even as her mental health visibly deteriorated, the government said, citing interviews with Mr. Dong and villagers. When she first arrived in Dongji, she had been able to take care of herself; by the time she was found, she had trouble communicating.

The government report did not say whether other villagers knew she had been trafficked. But self-styled charity bloggers had been visiting Mr. Dong and presenting him as a doting father since at least 2021. (The woman appeared in some videos, but unchained.)

“My biggest dream is to slowly bring the children up into healthy adults,” Mr. Dong told one blogger, before the video of the shack emerged.

Mr. Dong’s social media posts portray him as a doting father

Privately, though, Mr. Dong had been chaining the children’s mother around the neck and tying her with cloth ropes since 2017, the government said. He also did not take her to the hospital when she was sick.

Censors deleted the bloggers’ videos of the family and of the woman in chains. In April 2023, Mr. Dong was sentenced to prison, along with five others accused of participating in the trafficking.

The official story ended there.

Step 1: Hide the Victim

As we approached the house where the men were sitting, they jumped up and asked who we were. One made a phone call, while another blocked me from taking photos.

Ten more people soon arrived, including police officers, propaganda officials and the village leader, who insisted that the scandal had been overblown. “Everything is very normal, extremely normal,” he said. When we asked where the woman was, officials said they believed that she didn’t want visitors. Then they escorted us to the train station.

The chained woman may be choosing to stay out of the public eye. But the Chinese government often silences victims of crimes or accidents that generate public anger. Relatives of people killed in plane crashes, coronavirus patients and survivors of domestic violence have all been shuffled out of sight, threatened or detained.

Some weeks later, we tried to go back. This time, we visited a hospital where China’s state broadcaster said the woman was sent after the video went viral — her last known whereabouts.

We tracked down Dr. Teng Xiaoting, a physician who had treated her. Dr. Teng said the woman was no longer there, but said she did not know where she had gone.

Other locals we asked had no information either. But several people in neighboring villages said it was common knowledge that many women in the area, including in their own villages, had been bought from southwestern China. Some called it sad; others were matter-of-fact.

Still, it was clear that talking about such trafficking could be risky.

As we got closer to Dongji, a black Volkswagen began tailing us. Then, at least eight villagers surrounded us, calling us race traitors (we are both of Chinese heritage) and at times pushing my colleague. One said that if we had been men, they would have beaten us.

They eventually escorted us back to the main road after we called the police. Along the way, one man said it was in our own interest to be more cautious.

“If you two were taken to the market and sold,” he said, “then what would you do?”

Step 2: Silence Discussion

After the woman’s story emerged in January 2022, the controls were tightest in Dongji. But the government sprang into action across the country to suppress the debate that followed.

Legal scholars observed that the penalty for buying a trafficked woman — three years’ imprisonment — was less than that for selling an endangered bird. Others noted that judges have denied divorce applications from women known to have been abused or trafficked, and that the government has repeatedly ignored calls to criminalize marital rape.

To halt such conversations, the police tracked down people like He Peirong, a veteran human rights activist, who had traveled 200 miles to the area around Dongji to try to look for other trafficked women.

After she returned home, police officers knocked on her door, asking her why she had gone. They visited her roughly 20 times over the next month, forcing her to delete online posts about her trip and threatening to arrest her.

They also named journalists she had been in contact with, to show they were watching her communications. They even took her to nearby Anhui Province on a forced “vacation” — a common tactic used to control dissidents’ movements.

Similar crackdowns were taking place farther away. A lawyer named Lu Tingge, a resident of Hebei Province, about 600 miles from Dongji, said in an interview that a Jiangsu official had traveled to his city, urging him to withdraw a petition he’d submitted for more information about the case (he refused, but said he never received the information).

Bookstores that put up displays recommending feminist reading were forced to remove them. Numerous online articles about the woman were censored; China Digital Times, a censorship tracker, archived at least 100 of them, though there were many more.

The campaign even extended overseas. A woman living abroad said in an interview that the police called her parents in China after she posted photos of herself in chains online.

Ms. He, the veteran activist, realized that the government was more worried about feminism than she had thought. She had been detained previously for other activism, but this monthslong pressure “far surpassed that,” she said.

Step 3: Detain Those Who Persist

To avoid arrest, Ms. He stopped posting about the case. She eventually left China for Thailand.

Those who refused to stop, however, suffered the consequences.

Two other women also traveled to Jiangsu after the video emerged, to visit the chained woman at the hospital. Identifying themselves on social media only by nicknames, Wuyi and Quanmei, they said they were just ordinary women showing solidarity.

“Your sisters are coming,” Wuyi posted.

They were barred from entering the hospital or the village, according to videos on Wuyi’s Weibo. So they drove around town instead, with messages about the woman scrawled on their car in lipstick.

They quickly attracted enormous followings, their updates viewed hundreds of millions of times.

Before long, they were detained by the local police. After their release several days later, Quanmei went quiet online.

Wuyi, though, refused to be silenced. On Weibo, she said police had put a bag over her head and beat her. She shared a photo of her bruised arm, saying she was shocked that her small actions could elicit such ferocity.

“Everything I always believed, everything the country had always taught me, all became lies,” she wrote.

About two weeks later, Wuyi disappeared again. This time, the police detained her for eight months, according to an acquaintance. She was eventually released on bail and has not spoken publicly since.

The Resistance Goes Into Hiding

After Wuyi’s disappearance, the few voices still speaking out fell silent.

But the activism has not evaporated, only moved underground.

It includes people like Monica, a young woman who asked to be identified only by a first name. We met at her home, where she asked that I not bring my cellphone to avoid surveillance. Soft-spoken but assured, she recounted how police scrutiny forced her to embrace new tactics.

When the chained woman story erupted, she joined an online group of several hundred people that decided to conduct research on the trafficking of women with mental disabilities in China.

Within days, the police tracked down and interrogated participants. At around the same time, anonymous articles appeared online that doxxed some members of the group and labeled them “extreme feminists.” The group disbanded.

But the intimidation only made Monica angrier.

So a few months later, Monica and several others quietly regrouped, using an encrypted messaging platform. Rather than campaign publicly, they tried to impose pressure on the government behind the scenes.

For weeks, they studied hundreds of court cases and news stories about women who had been abused or trafficked. They wrote a 20-page report explaining the chained woman episode and laying out suggestions for reform. In July 2022, they submitted it anonymously to a U.N. committee reviewing China’s record on disability rights.

They later submitted similar reports to two other U.N. committees. A member of one of the committees, speaking anonymously because of the sensitivity of the matter, said the reports were crucial sources of independent information from China. That person had not heard of the chained woman before.

In May 2023, U.N. officials raised the chained woman’s story during a public meeting with Chinese government representatives. The government said it had imprisoned Mr. Dong and that the woman was being cared for. Still, Monica felt proud — and emboldened: “You feel that you can still do some risky things.”

“Feminism in China really is the most vocal and active movement. It’s also very hard to completely scatter or kill off,” she said. “I think the authorities are right to be worried.”

Others have tried to subtly keep the chained woman’s legacy alive in other ways. An all-female band released a song called “So Who Has My Key?” An artist spent 365 days wearing a chain around her neck. A writer published a thinly disguised retelling of Snow White.

In December, a woman whose family had reported her missing 13 years ago was found living with a man to whom she had borne two children. The authorities claimed the woman had a disability and the man had “taken her in” — the same language officials used in an early report about the chained woman.

Social media users erupted, accusing the government of glossing over trafficking again.

Then the censors stepped in and stifled that discussion, too.

Siyi Zhao contributed research.