A rural doctor travels miles of unforgiving terrain by donkey, enduring cold, rain, wind and exhaustion, to visit several dozen families scattered across the highest mountain in the north of Argentina.

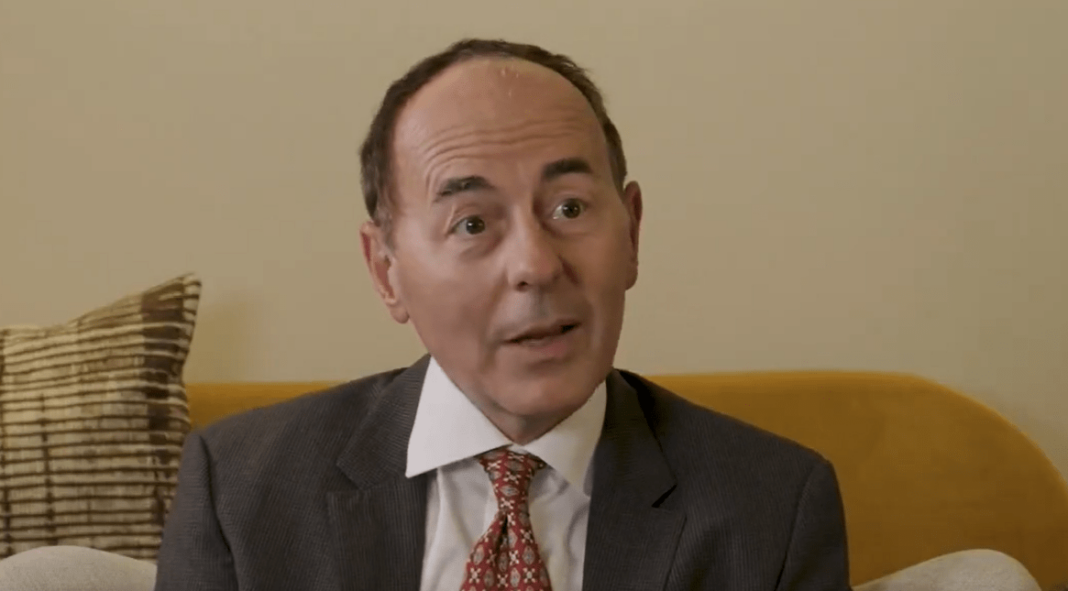

Dr Jorge Fusaro has organised medical tours three times a year for the past four years across Cerro Chani in Jujuy. Chani is considered a sacred mountain by the Indigenous Kolla people who live there. It has extreme temperatures and year-round snowy peaks, and is home to animals full of symbolism, like the puma and condor.

Fusaro is not only the only doctor many people see, sometimes he is the only outsider.

Doctors may be the only representatives of the state to reach this mountainous region. There are no schools, police or postal services. Fusaro not only treats residents and leaves enough medicine for their first-aid kits, he also helps them with bureaucratic paperwork, serves as a mail carrier for delivering important documents to relatives in the city, and organises training sessions, among other tasks.

“Knowing that our medical work gave these communities a better life fills my heart. If we don’t go, no one will,” says the 38-year-old doctor. He’s worried that government cuts will make future trips impossible. He’s already had to cancel one trip due to lack of funding.

For some people, his arrival is the first time they’ve seen a doctor. They are surprised that he keeps coming back.

It’s almost noon, and the sun blazes down at nearly 3,600m (11,800 feet) above sea level in Ovejeria, a settlement where only 67-year-old Dona Virginia Cari, her husband Eustaquio Balderrama, and their son Panchito remain.

In a kitchen with a thatched roof, Fusaro chops onions and peels potatoes to help Virginia prepare lunch. He asks her about her daily chores, her animals, her husband’s health, the weather, her children living far away, and her medicinal plants.

“My idea of sharing is essential. Making the most of the short time we spend in the communities and trying to live as they do; if we need to chop wood or walk for hours to fetch water, we do it,” he said.

“That way, we understand their efforts and worries, their knee or back pain. If they don’t have a bed and we need to sleep on a sheep’s hide, we do it; if they only have soup at night, we drink soup. This helps us think of medical solutions within their possibilities and daily lives.”

Virginia says it’s important for her and her family to see this rural doctor a few times a year.

“I’m very happy when I see the doctor arrive on his mule. He brings the medicines we take here for months,” she said. “The work with animals is hard; we’re old, and our bodies ache.”