Culture — a word we toss around a lot. Too often though, it gets boxed into clichés and stereotypes. It’s more than language, fashion, music, or food, it also shapes how we see the world and, more importantly, how we find each other in it.

There was a time when giants like Pepsi, Hollywood, or even Disney shaped the pulse of global culture, but today’s landscape tells a different story. Nowadays, the rise of micro-influencers — an influencer best known within a niche community — and rising brands by small business owners have made it impossible to define culture through a single, universal lens.

Audiences today aren’t all tuning into the same show, listening to the same music, or rallying around the same global brands like they once did. The idea of a single, unified mainstream culture has fractured over time, giving way to a rise in subcultures, which are alternative to the conventional norm. In the music world, for example, while pop music used to dominate the mainstream, subcultures rooted in Latin, Arabic, and African sounds have grown in popularity.

Nour Abosaif and Aisha Aldris, founders of Culture Mocktail—a brand and platform centered on cultural identity and belonging—are riding the global wave of rising subcultures. Their work reflects a growing desire for media, brands, and art that speak directly to cultural roots and personal identity.

Blending card games, workshops, and candid conversations on their podcast, they invite a new take on cultural identity, introducing a more layered perspective that resonates with today’s generation and a growing population of people who have been influenced by multiple cultures.

For Abosaif and Aldris, culture is, above all, about connection; one that goes beyond geography. It links us to people, to shared histories, to stories passed down, and to memories that shape who we are.

But, that sense of connection hasn’t always come easily to them. Growing up in the Western environments — Abosaif in international schooling and Aldris in the UK — they often felt misunderstood in environments that are shaped by stereotypes and racist assumptions about Arab culture, where the complexity and value of cultural identity were rarely acknowledged, making it harder to feel truly seen.

As Islam is now the second-largest religion in the UK, there’s been a noticeable rise in misunderstandings and harmful stereotypes—especially those that unfairly link Muslims to violence. In light of this, it’s more important than ever to encourage thoughtful education around culture and cultural differences.

Below, Egyptian Streets sat down with the founders of Culture Mocktail to explore what culture truly means and how brands can more authentically represent Arab identity.

Can you describe a time during your upbringing when you felt disconnected from your culture?

Nour: I spent the first 14 years of my life outside of Egypt, growing up in the Gulf. We’d go to Egypt in the summers, but I never felt like I really fit in. I always felt like a foreigner—even though I was technically ‘home.’ My cousins would joke around and call me khawaga (foreigner) because of how I spoke, or how I didn’t quite act like someone who lived in Egypt. It was playful, but also made me feel like I was somehow not Egyptian enough.

When I moved to Cairo at 14 for high school, I thought it would be different. I was excited to finally live in Egypt and make Egyptian friends. But I quickly realized that there’s a real difference between Egyptians who live abroad and those who grow up in Egypt. The culture, humor, interactions—it was all unfamiliar. I didn’t click with the Egyptian students at school and ended up becoming closer with the foreigners, which just deepened the feeling that I didn’t really belong anywhere.

Aisha: During high school, I definitely felt disconnected from my culture. I went to a predominantly white school in a city where 95 percent of the population was white—that’s official census data. For a while, I was the only Arab and the only hijabi in my school, and it was really difficult.

At that age, you just want to fit in. You don’t want to stick out—you want to blend. And for me, that meant pushing away parts of myself. I wanted to hide my culture to avoid standing out, and looking back, that’s such a shame. But I also think it was something I had to go through to come out the other side.

It wasn’t until I left home for university that I began reconnecting. I started to really engage with my culture again. I found myself trying to recreate the feeling of home—and home, to me, was culture.

Can you share an example of a card game by Culture Mocktail that helped to create stronger connections between cultures?

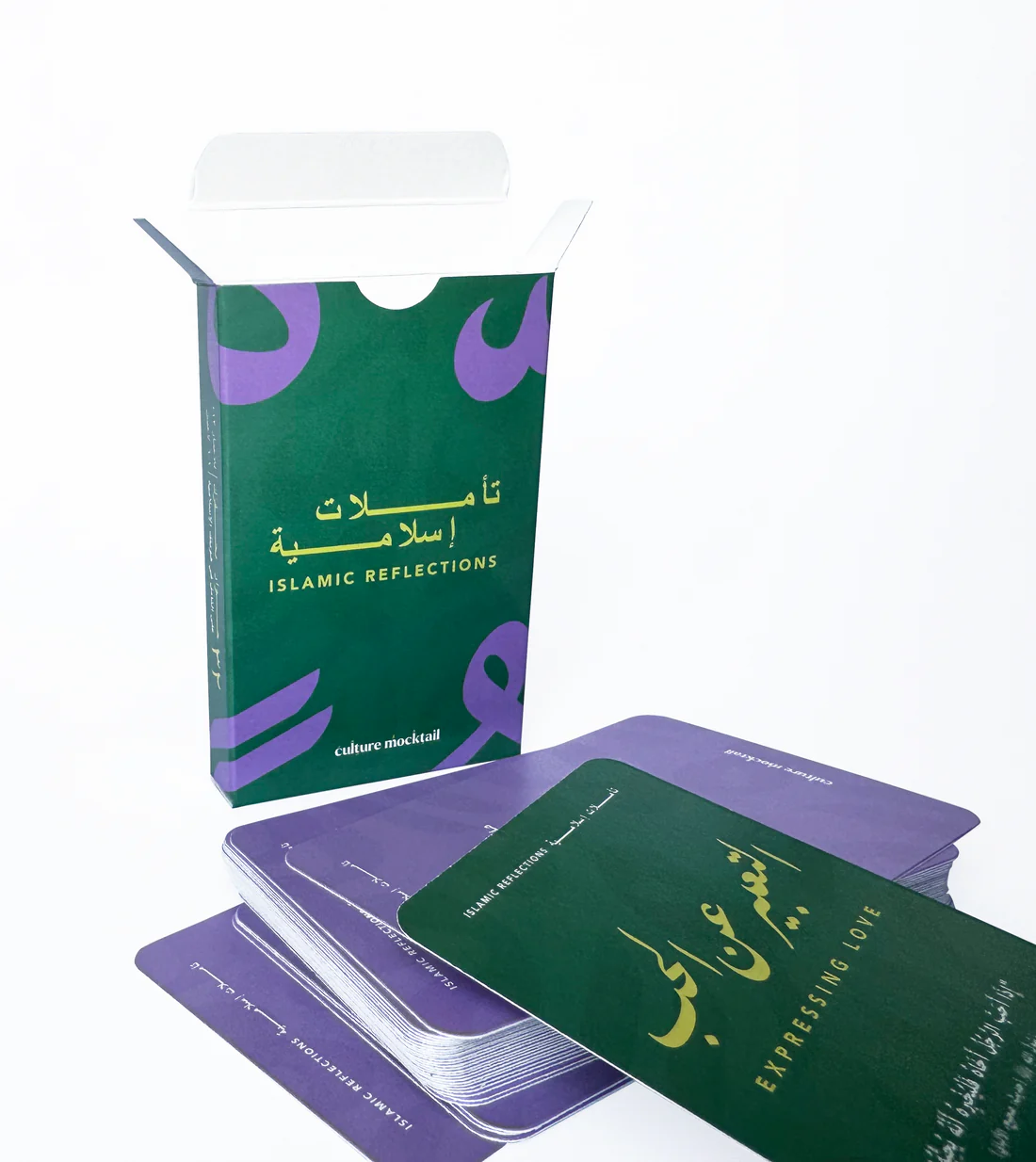

Nour: One of our most meaningful creations is Islamic Reflections, a card game designed to spark heartfelt conversations around Islamic teachings. Each of the 32 cards features a teaching sourced from the Quran or Hadith on one side, and thoughtful, open-ended questions on the other. We wanted to create something that felt inviting and loving, not rooted in fear or rigidity. A space for reflection, curiosity, and genuine connection.

The response has been incredibly moving. One woman from Peru, who isn’t Muslim, shared that she bought the game to start conversations about Islam in her own community. That moment stayed with me; it reminded me how culture, when approached with openness, can transcend borders, beliefs, and backgrounds. It’s powerful to see something so simple become a bridge between worlds.

Culture Mocktail’s card games are available for purchase online through our website and in-store at Maison69 in Zamalek, Cairo.

Can you share examples of misunderstandings around cultural differences? How do you define culture, and how is it different from these superficial interpretations?

Nour: When I moved to the UK for university, I faced a lot of assumptions. People were surprised I spoke fluent English, and some even asked if I was Canadian, as if an Arab couldn’t be educated or global.

As a hijabi Muslim woman, I also got questions like, “Did your dad let you move here alone?” or “Are you allowed to go out by yourself?”—reflecting the stereotype that Muslim women lack autonomy. But my experience of Islam has always been rooted in love, trust, and strength.

When it comes to defining culture, I think it’s so much more than just henna or food or fashion. Those things are beautiful, but they’re surface-level. Culture is how we make sense of the world. It’s the practices, beliefs, language, and even the emotional logic that binds a community together. Even within Egypt, there are so many subcultures—Nubian, Sa’idi, urban Cairo culture. So when we say ‘Egyptian culture,’ we’re actually talking about many experiences. It’s not one-size-fits-all.

Aisha: Sure, culture can be in the clothes we wear or the music we listen to, but it’s also in how we express love, how we welcome guests, how we communicate, how we live. I think sometimes people miss that depth. Especially with third-culture kids, like myself, we end up creating our own hybrid cultures from all the places and people we come from.

Culture can evolve, but it always speaks to values—it’s carried in kindness, in community, in rituals, and even in the ways we break away from tradition. To me, culture is in everything. It’s not just a look—it’s a legacy.

Many people think culture is purely shaped by family values, assuming it limits individual identity. Can you explain how culture has empowered you as an individual?

Nour: I used to see Arab culture—especially its collectivist side—as limiting. It felt like everything was about reputation, family expectations, and hiding parts of yourself to fit in.

But through our work at Culture Mocktail, especially workshops like Unpacking Arabic Expressions, I began to understand the depth behind those values. Arabic has over 12 million words—so much nuance and emotion. That opened my eyes to the richness of our culture.

Now, I see culture not as something that takes away from who I am, but something that adds to me. It’s made me feel more whole—not like I have to choose between the two, but that I can exist in the in-between.

Aisha: Living between cultures is definitely a journey, but it’s also incredibly freeing. You learn to embrace all parts of yourself and take the best from each culture. That, in itself, gives you a kind of peace—you stop trying to fit into one place or box.

There’s so much power in that acceptance—in knowing that your identity is layered, and that it doesn’t need to be diluted or simplified to make sense to others. That realization brought me a lot of personal peace.

Some assume that being deeply connected to your culture means rejecting or being judgmental of other cultures, especially Western ones. Can you explain how that’s a misconception?

Aisha: I think some people assume that cultural pride equals exclusion or hate, but often it’s just people sharing their own stories and experiences. And yes, sometimes that includes criticism—especially of Western histories that have harmed communities. But holding those systems accountable isn’t the same as being judgmental or generalizing people or cultures as a whole.

There’s a difference between genuine critique and outright dismissal. Many people who speak about the oppression they’ve experienced are simply telling the truth of their lives, not condemning an entire culture. It’s important to make that distinction.

Why should brands pay more attention to Arab culture?

Nour: Culture shapes everything, from how we eat, to how we move, what we wear, how we shop. Brands should care about Arab culture not just because of our buying power—which is massive—but because we deserve to be seen in ways that are real. A lot of brands are just now starting to pay attention, but they often do it in ways that feel superficial. It’s not enough to just put a hijabi in your ad during Ramadan. If you want to connect with our culture, you need to co-create with us.

Aisha: Being Arab and Muslim has made me more conscious of how I dress and where I shop—especially now, in light of the genocide in Gaza. I’m more intentional about boycotting brands and aligning my purchases with my values.

As for brands, rather than just “appreciating” Arab culture, I think the focus should be on platforming Arab people. Our culture is rich in history, soul, and beauty, and deserves to be represented by us, not just styled by others. Every culture has a story that’s worth sharing, and ours is no exception.

Do you believe Western brands are starting to pay attention to cultural influences in meaningful ways?

Nour: Some are, but most aren’t there yet. I saw a recent Coach campaign with Palestinian artist Elyanna and it just didn’t sit right with me. It felt like they were trying to speak to us, but hadn’t done the work. It was all aesthetics and no substance.

On the flip side, we were part of a collaboration with the Victoria and Albert Museum in London through Culture Mocktail, and that experience couldn’t have been more different. They recently hosted a major event with a collective called Muslim Sisterhood, who are a community and creative agency who unapologetically celebrate Muslim identities. We also had a pop-up at the event’s 3EIB games room. 3EIB are a community-led fashion platform and a pop-up series focused on creating a safe space for Arab creatives. The entire collaboration felt like a huge celebration of identity and it’s just incredible to work with brands that genuinely get it.

And that’s because they did the work. They had people of color on their team, they did the research, and most importantly, they invited us—the very communities being represented—to co-create with them from the beginning. They didn’t just market to us—they built with us. That’s what makes all the difference.

Aisha: It’s not just about what a brand puts on a billboard or campaign. It’s about whether their business practices actually reflect the culture they’re claiming to support. That’s where the real work begins. If a brand truly wants to engage with a culture, it needs to understand that culture’s history, its current struggles, and its values.