When someone asks, “Where are you from?”, the answer is often simple: just the name of a country. But for many migrants displaced by war, it is no longer answered with the name of a country, but with a story. A story of loss, movement, and survival.

For them, home becomes something that is felt rather than found, evoked by a smell in the air, a sound in the distance, or a moment that passes too quickly to hold. Even if home can no longer be pinpointed on a map, many migrants carry it with them in other ways, such as through memories, objects, scents, and fleeting sensations that recreate a mental geography only they can navigate.

This deeply personal sense of place was at the heart of an evocative exhibition titled “From the image, we build walls, a roof and windows,” held at the French Institute in Cairo in collaboration with Kalam Aflam – an association dedicated to nurturing Arab arts and supporting emerging voices from the region.

Among the participating artists were Palestinian artist Amal Al-Nakhala and Sudanese artist Ola Mohamed, both of whom recently arrived in Cairo following the outbreak of war in their home countries. Since then, they have been grappling with the emotional weight of displacement and the uncertainty of ever returning home.

The exhibition was the culmination of a multi-week collaborative workshop led by Tunisian visual artist and researcher Aya Chriki, who guided participants in transforming personal narratives of displacement into powerful visual installations, turning absence into presence, and memory into form.

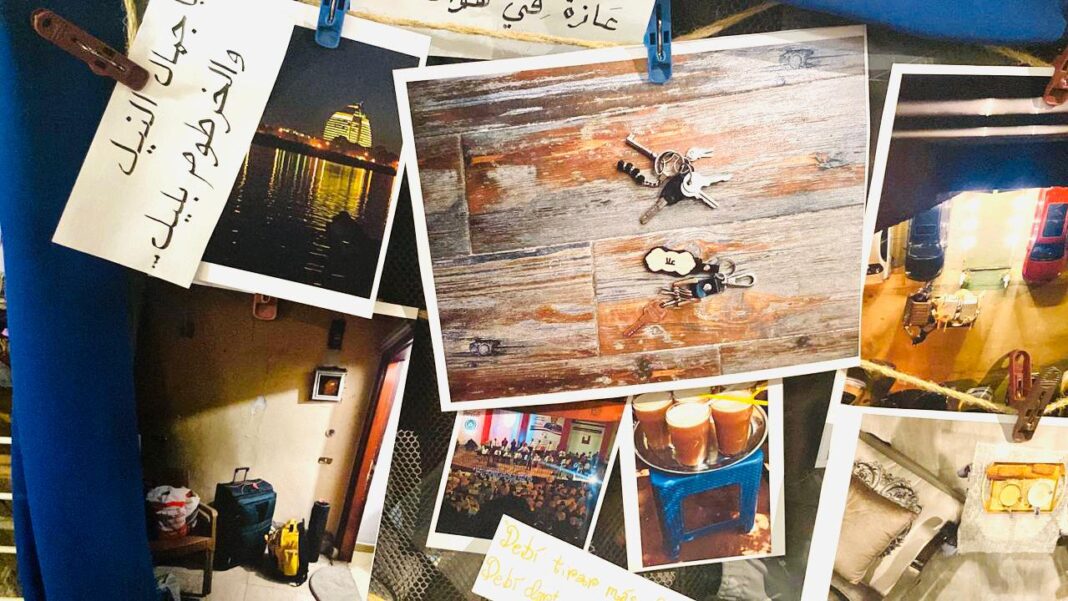

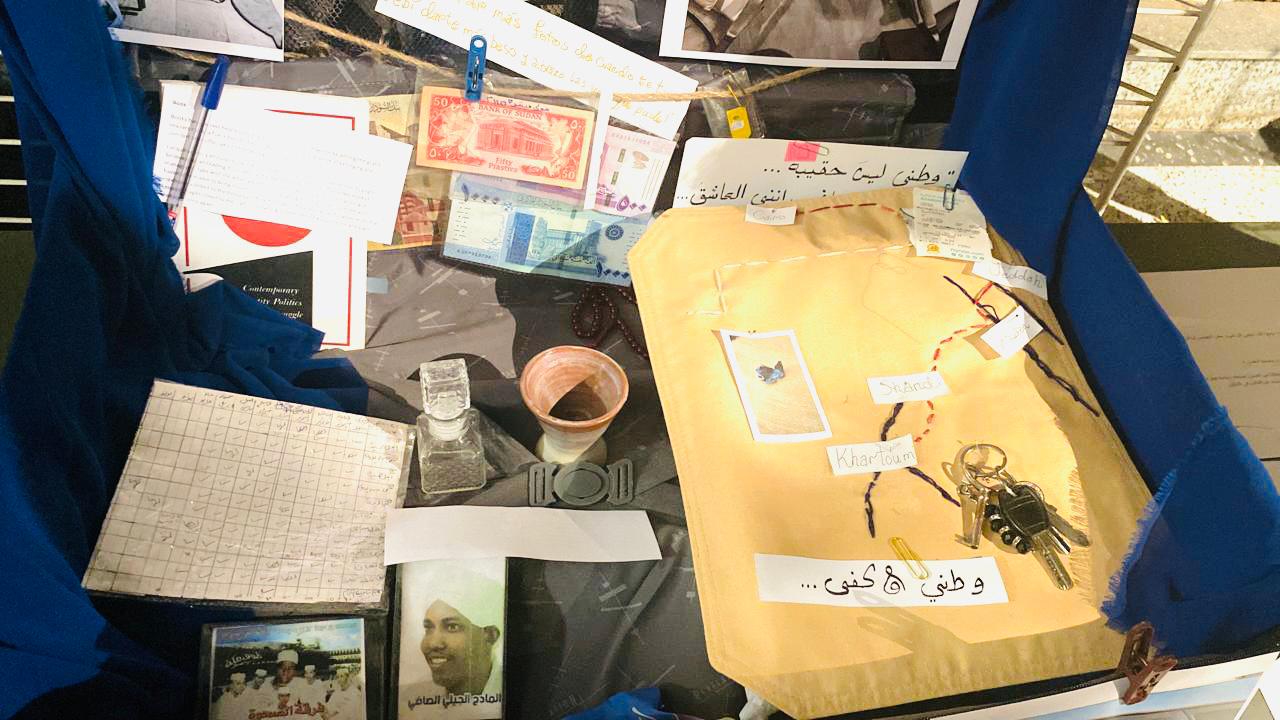

Bringing together the work of eleven visual artists – Egyptian and migrant women currently living in Cairo – the exhibition invited audiences into the intimate spaces of their migration journeys. Each artist opened a symbolic suitcase, filled not just with physical objects, but with fragments of memory: photographs, scents, poetic verses, and drawings.

These suitcases became vessels of loss and repositories of memory. For some artists, they were filled with tangible traces of home: passports, family photographs, handwritten notes, which are physical tokens of a life left behind. Yet for others, the contents were more abstract, fragmented expressions of grief and longing.

Through emotional poetry, illustrations, and raw visual metaphors, the art installations gave form to the sorrow that words alone could not hold, revealing the weight of a home that now exists only in memory and feeling.

On Gaza, Memory, and a Shifting Sense of Home

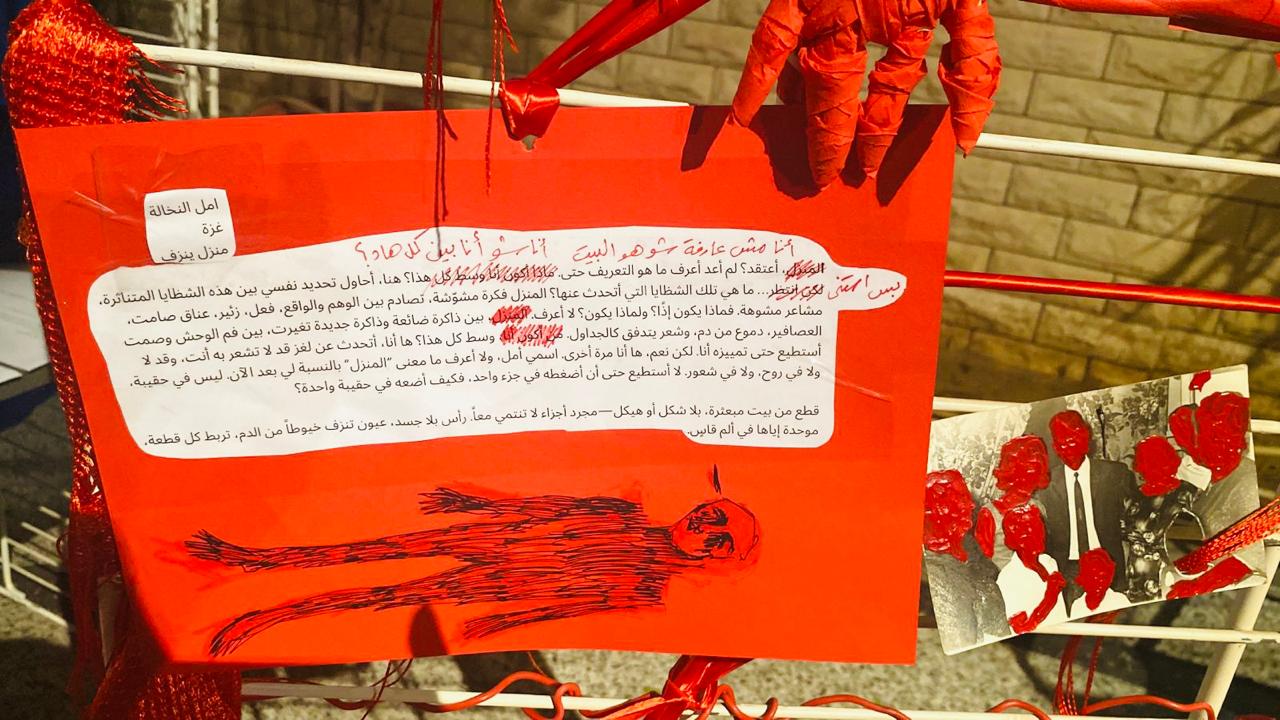

For Palestinian artist Amal, the idea of home is neither static nor whole; it is a disjointed memory, a fractured feeling, a concept in constant motion. A year and two months after fleeing Gaza for Cairo, she speaks with layers of exhaustion and pain.

“Home used to be something I imagined in my head,” Amal says to Egyptian Streets. “Like, mom cooking in the kitchen, the smell of food. But that was just an illusion. The reality was never like that,” she continues.

Amal arrived in Cairo in February 2024, after being displaced seven times within Gaza. “The first three days of war, we stayed,” she recalls. “Then the bombing started, right in front of us. We had no choice but to evacuate.”

Her journey was marked by constant movement. “We changed places six times. I remember telling my mom at one point, ‘The more we move, the further we are from Gaza.’ And at the border, I said to her, ‘Mama, we’re not going back. We’re just getting farther and farther away.’”

That feeling – of leaving without return – has lingered. “We spent 19 hours at the border. Then it took eight more hours to get to Cairo. When I arrived, I didn’t even look back. I still feel like I’m evacuating, like I haven’t stopped moving.”

But in Cairo, Amal’s sense of home has become abstract. Her art – bleeding with symbolism and pain – reflects that.

“When I’m dislocated, I don’t pack memories. I pack papers, such as documents I might need. Everything else is destroyed,” she says. “So I use objects to symbolize home. A bleeding heart. A cloud in a red sky. A burned, amputated hand.”

One of her installations features a family portrait she found in a flea market, its faces smeared with blood, anonymized. “I don’t know who they are. But I erased their features to reflect how the concept of family itself has become meaningless to me. Home, memory, family—nothing is connected anymore.”

This disorientation is the very language of her work. “The objects I use aren’t related. That’s the point,” she says. “It’s how I describe the feeling of being detached, of not knowing where I belong.”

Growing up in Gaza, destruction was a part of life, she shares. “Even as a child, I was used to seeing buildings fall. It’s not new to me,” she says. “So now, when I think of home, I don’t even have a vision for it. It’s a concept that keeps changing—shifting from one version of itself to another.”

The past year in Cairo has reshaped that vision further. “If I ever return to Gaza, I know it won’t feel the same. It’ll be completely different from how I feel about it now,” she says. “Because I’ve changed. Home has changed. The destruction has left its mark.”

For her, coping is not a choice, and resilience cannot be romanticized. “I am forced to cope,” she says. “There is no other option.”

As wars continue to redraw lives across Palestine, Amal hopes people will begin to understand that displacement is not only a matter of movement; it’s a complete erasure of certainty, of memory, and of self.

“I want people to know that for some of us, home is not a place we can go back to,” she says. “It’s a feeling we’re still trying to reassemble from ruins.”

Finding a Second Home in Cairo

While Amal’s suitcase held no physical mementos, instead reflecting the emotional disorientation of displacement, Sudanese artist Ola’s suitcase told a different story. Hers was filled with tangible fragments of home – photographs taken along her migration journey, the familiar scent of cherished items, and even her house keys.

Among the most poignant inclusions was the ritual of Shai Laban bi Baskaweet – milk tea with biscuits – a simple Sudanese tradition that, for Ola, offered a sense of grounding and comfort. Even far from Sudan, it allowed her to momentarily reclaim the feeling of home.

What binds Amal and Ola’s installations, however, is the understanding that home is not a fixed place; it is a feeling, ever-shifting and deeply personal. It’s not bound by borders or rooted in architecture, but by something more elusive — something she carries with her through the people she loves, the memories she holds, and the fragments of comfort she’s managed to gather along her journey.

Ola now lives in Cairo after fleeing Khartoum in May 2023 when the war broke out in Sudan. What followed was a harrowing journey of displacement marked by fear, separation, and uncertainty. She still recalls the early days of the war vividly.

Since the onset of the Sudanese civil war in February 2023, Egypt has seen a significant influx of migrants. Today, it stands as the largest host of Sudanese refugees.

“We were living in Khartoum when it all started, right next to the military headquarters. There were gunshots constantly, bullets even reached our home,” she says to Egyptian Streets, holding up a photo of a bullet fragment. “It became too dangerous to stay, so we moved to a family house in Shenbi.”

But Shenbi, crowded with more than 50 relatives seeking refuge, couldn’t hold them for long. The family then relocated to an empty house in Port Sudan, hoping for a semblance of safety. Ola eventually left Sudan alone, flying through Jeddah before landing in Cairo, driven by the urgency of an upcoming exam and visa restrictions. Her mother and brother followed many weeks later after delays and border troubles.

The dislocation was more than just physical, it was also emotional, marked by the ache of uncertainty and the fear of being separated from her family indefinitely. “I left my country without my family, not knowing when I’d see them again,” she says. “They were stuck on the border, literally sitting in the streets.”

Two years later, Ola still finds herself wrestling with the idea of belonging. The Cairo she lives in is both a refuge and a reminder of what she’s lost.

“There are days I think, ‘Okay, I can do this. I can live here.’ Cairo has given me a kind of second home,” she explains. “But at the same time, I face racism and rejection on a daily basis. People curse at me in the street, tell me to go back to my country. I feel like I’m constantly having to prove I belong.”

Workshops and artistic communities have provided pockets of relief – spaces where she can reflect, create, and connect with others who understand displacement intimately.

“I wrote a poem during that workshop. I realized I’d been so angry with Sudan, angry for the years I protested, got arrested, got hurt, and received nothing in return,” she says. “But when the war came, I understood just how much I loved it. And just how much I’d lost.”

Still, she admits, the thought of returning to Khartoum is complicated. “Right now, Sudan is tied to pain. It’s full of memories of fear, of running. So when people ask if I want to go back, I don’t know. I’ve found something here, in Egypt. It’s not perfect. But it’s something.”

That “something” is layered: fellow Sudanese friends, shared struggles, the empathy of a few kind strangers. It’s enough to keep her grounded – for now.

Ola has been waiting over a year for her residency permit, making it difficult to move freely or even consider travel. “It’s terrifying,” she says. “I can’t leave the country. I’m scared I’ll get stopped.” Despite everything, she remains hopeful, and wants others to understand the complexity of the Sudanese experience.

“There’s a misconception that all Sudanese people are the same or that we’re just here to take,” she says. “But we’ve suffered, deeply. We’ve been through revolutions, wars, heartbreak. What I want is for people to talk to us, to ask questions, to listen.”

She continues, “There’s such a diversity in Sudan. Just recognizing that – that we are not one narrative – can make a huge difference in how we’re treated and understood.”

For Ola and many other migrant artists in the exhibition, home may never be a single dot on a map again. But in their family’s embrace, the resilience of their community, and the stories they share through their art, they have found something more enduring: a glimpse of what home feels like, even if it is brief.