Uganda is gearing up for general elections in January 2026 – the seventh since President Yoweri Museveni came to power in 1986. As in the lead-up to previous polls, repression is on the rise. This time, however, it has extended beyond Uganda’s own borders.

On November 16, 2024, opposition politician Kizza Besigye and his aide Obeid Lutale were abducted in Nairobi, Kenya. Four days later, they resurfaced in Uganda’s capital Kampala arraigned in a military court on security charges. Rendered to Uganda, in clear violation of international laws prohibiting extraordinary rendition and due process, the two civilians faced military justice.

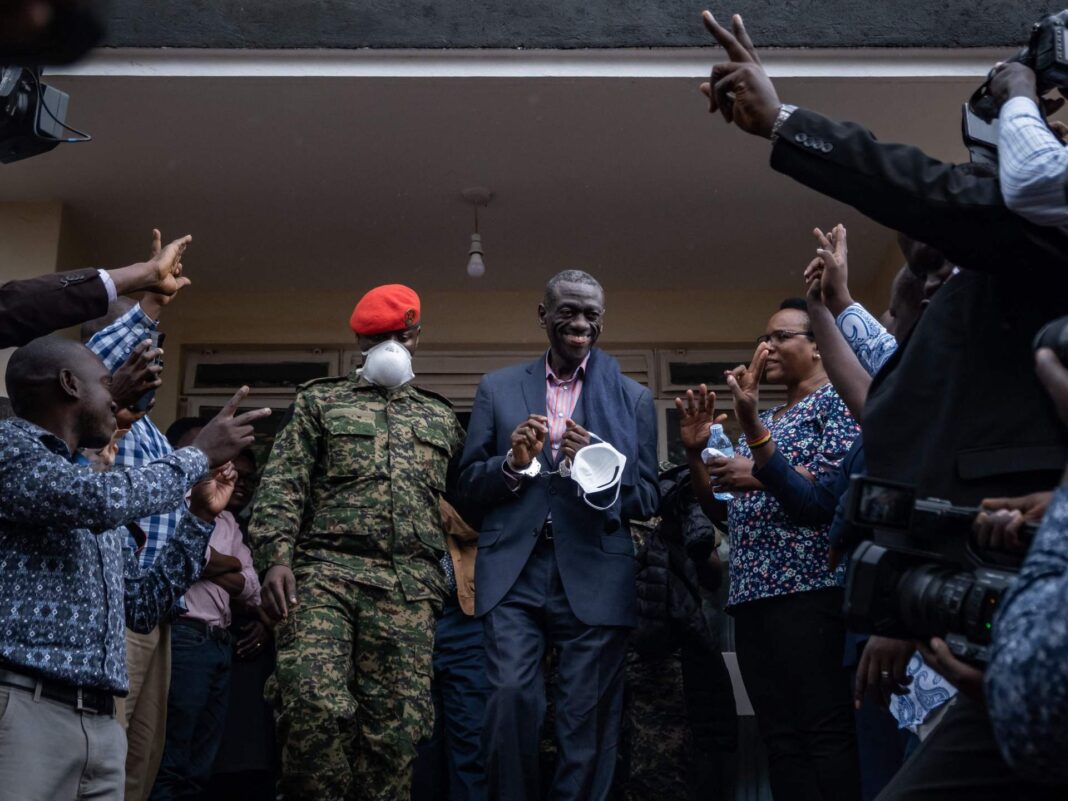

Outraged by this militarisation of justice, Besigye and Lutale attracted a 40-strong defence team led by Martha Karua, Kenya’s former minister of justice.

If the state antics were intended to silence dissenting voices, they have done just the opposite. Far from dissuading others from speaking up, these trials have sparked a national conversation on human rights and the role of the military.

Uganda’s Chief of Defence Forces (CDF), General Muhoozi Kainerugaba, Museveni’s son, has regularly commented on Besigye’s case on X. Widely seen as a potential successor to his ageing father, Kainerugaba heads a political pressure group, the Patriotic League of Uganda (PLU), despite legislation currently prohibiting serving military officers from involvement in partisan politics.

Since 2016, Uganda’s Supreme Court had delayed ruling on a case, brought by Michael Kabaziguruka, a former member of parliament, challenging the trial of civilians before military courts. Kabaziguruka, who was accused of treason, argued that his trial in a military tribunal violated fair trial rights. As a civilian, he contended he was not subject to military law. Besigye and Lutale’s case gave renewed impetus to this.

On January 31, 2025, the Supreme Court ruled that trying civilians in military courts is unconstitutional, ordering that all ongoing or pending criminal trials involving civilians must immediately stop and be transferred to ordinary courts.

Despite this ruling, President Museveni and his son have vowed to continue using military courts in civilian trials. Besigye went on hunger strike for 10 days in protest against delays in transferring his case to an ordinary court. The case has now become a litmus test for Uganda’s military justice system ahead of the 2026 elections.

Besigye and Lutale are not the only opposition politicians to face military justice. Tens of supporters of the National Unity Platform (NUP), led by Robert Kyagulanyi, popularly known as Bobi Wine, have been convicted by military courts for various offences. These include wearing NUP’s trademark red berets and other party attire that authorities claimed resembled military uniforms, despite their distinct differences. Numerous lesser-known political activists are facing charges in military courts, too.

Over 1,000 civilians have been prosecuted in Uganda’s military courts since 2002 for offences such as murder and armed robbery.

For context, in 2005, the state amended the UPDF Act to create a legal framework which allowed the military to try civilians in military courts. It was no coincidence that these amendments happened as the military was trying civilians arrested between 2001 and 2004, including Kizza Besigye.

Military trials of civilians flout international and regional standards. They open possibilities of a flurry of human rights violations, including coerced confessions, opaque processes, unfair trials and executions.

Trying civilians in military courts violates Article 7 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights and the 2001 Principles and Guidelines on Fair Trial and Legal Assistance in Africa. The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, the region’s premier human rights body, has long condemned their practice in Uganda.

Opposition to military justice has not just come from the usual quarters. Religious leaders expressed concern about Besigye’s continued detention after the Supreme Court ruling, as did Anita Among, speaker of Uganda’s Parliament and member of the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM), who remarked: “Injustice to anyone is injustice to everybody. Today it is happening to Dr Besigye, tomorrow it will happen to any one of us”.

Following the court order and widespread outcry, Besigye and Lutale were transferred to a civilian court on February 21. Besigye called off his hunger strike. They remain in detention, as does their lawyer. However, their transfer without release, in a process begun by an illegality, remains flawed. Despite the transfer of their case, scores of more civilians have their cases still pending before military courts, with little hope that they will be transferred to civilian courts.

For this reason, 11 groups including Amnesty Kenya, the Pan-African Lawyers Union, the Law Society of Kenya, the Kenya Human Rights Commission and Kenya Medical Practitioners, Pharmacists, and Dentists Union (KMPDU) call for their immediate release.

As Uganda approaches elections, it is evident that the military courts are now a tool in President Museveni’s shed for use to silence dissent. It is time for Uganda to heed the Supreme Court ruling – for now though, military justice is on trial, too.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.