Mario Vargas Llosa, the Peruvian novelist who combined gritty realism with playful erotica and depictions of the struggle for individual liberty in Latin America, while also writing essays that made him one of the most influential political commentators in the Spanish-speaking world, died on Sunday in Lima. He was 89.

His death was announced in a social media statement from his children, Álvaro, Gonzalo and Morgana Vargas Llosa.

Mr. Vargas Llosa, who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2010, gained renown as a young writer with slangy, blistering visions of the corruption, moral compromises and cruelty festering in Peru. He joined a cohort of writers like Gabriel García Márquez of Colombia and Julio Cortázar of Argentina, who became famous in the 1960s as members of Latin America’s literary “boom generation.”

His distaste for the norms of polite society in Peru gave him abundant inspiration. After he was enrolled at the age of 14 in the Leoncio Prado Military Academy in Lima, Mr. Vargas Llosa turned that experience into his first novel, “The Time of the Hero,” a critical account of military life published in 1963.

The book was denounced by several generals, including one who claimed it was financed by Ecuador to undermine Peru’s military — all of which helped make it an immediate success.

Mr. Vargas Llosa was never fully enamored, however, by his contemporaries’ magical realism. And he was disillusioned with Fidel Castro’s persecution of dissidents in Cuba, breaking from the leftist ideology that held sway for decades over many writers in Latin America.

He charted his own path as a conservative, often divisive political thinker and as a novelist who transformed episodes from his personal life into books that reverberated far beyond the borders of his native country.

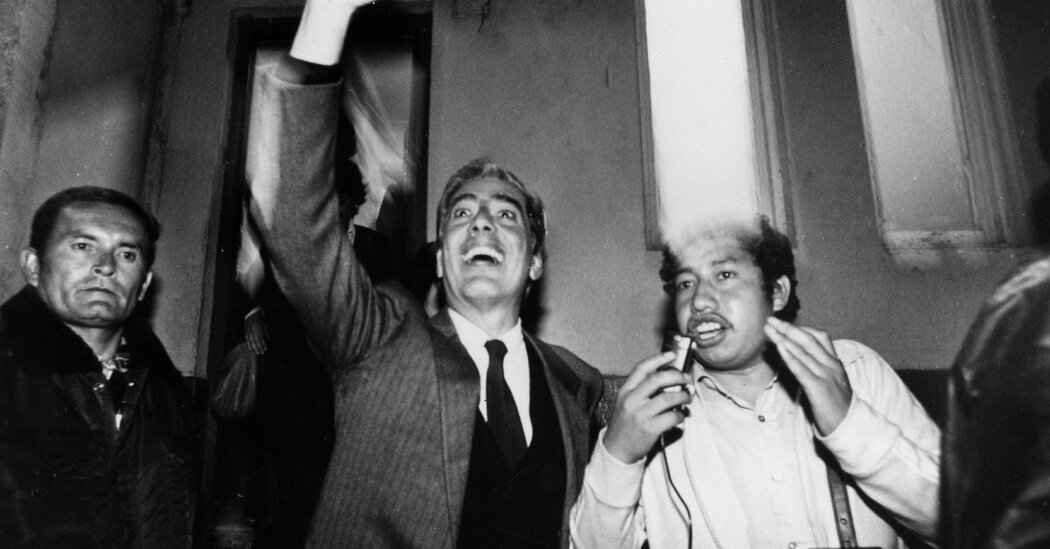

His dabbling in politics ultimately led to a run for the presidency in 1990. That race allowed him to champion the free-market causes he espoused, including the privatization of state enterprises and reducing inflation through government spending cuts and layoffs of the bloated civil service.

He led polls for much of the race, but was roundly defeated by Alberto Fujimori, then a little-known agronomist of Japanese descent who later adopted many of Mr. Vargas Llosa’s policies.

Mr. Vargas Llosa had a passion for fiction, but he started out in journalism. As a teenager, he was a night reporter for La Crónica, a Lima daily, chronicling an underworld of dive bars, crime and prostitution. Elements of that experience fed into his 1969 novel “Conversation in the Cathedral,” a depiction of Peru’s malaise under Gen. Manuel Odría’s military dictatorship during the 1950s, a book that is often considered his masterwork.

And though he often wrote articles for newspapers in Europe and the United States, he experienced a journalistic rebirth in the 1990s as a columnist for the newspaper El País in Spain, where he had been granted citizenship.

His fortnightly column, “Piedra de toque,” or “Touchstone,” was syndicated in Spanish-language newspapers throughout Latin America and the United States. It gave him a platform for topics like the re-emergence of populism in the Andes, the art of Claude Monet and Paul Gauguin or vociferous support for the state of Israel, a frequent theme in his political writing.

The columns could be either autobiographical or inspired by news events, and were often bereft of adjectives and elegantly written in a style that allowed Mr. Vargas Llosa to reach out to readers who might not have had the patience to finish some of his longer, complexly crafted novels.

“We do have a number of venerable newspaper columnists in the United States, but who among them has the stature of Vargas Llosa in Hispanic civilization?” the literary critic Ilan Stavans wrote in a 2003 analysis of the columns. “He’s a polymath who wears his wisdom lightly, with eyes and ears everywhere and a voice as loud as thunder.”

Perhaps more than anything, the columns allowed Mr. Vargas Llosa to advance his ideas of how personal liberties rely on the creation and strengthening of societies based on free trade.

He often drew derision for these principles in Latin America, ranking among the most prominent critics of leftist governments in Venezuela and Cuba.

But free-market thought held an almost visceral attraction for him. When Margaret Thatcher, Britain’s conservative prime minister, left office in 1990, she received flowers from Mr. Vargas Llosa. He also sent a note, reading, “Madam: there are not enough words in the dictionary to thank you for what you have done for the cause of liberty.”

Jorge Mario Pedro Vargas Llosa was born on March 28, 1936, in Arequipa, in southern Peru, and spent much of his early childhood in the Bolivian city of Cochabamba with his mother, Dora Llosa, and his grandparents. They made up a middle-class family of modest means but patrician ancestry, and he was told his father was dead.

His parents had actually separated months before he was born, and his father, Ernesto Vargas, who worked for the airline Panagra, took an assignment abroad and requested a divorce from his wife.

They reunited in Peru when their son was 10. But chafing at the discipline meted out by his father, the boy was soon sent to the military academy in Lima. After that experience, at the age of 19, Mr. Vargas Llosa eloped with Julia Urquidi Illanes, his uncle’s sister-in-law, who was 29.

The turbulent marriage shocked his family and inspired him to write “Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter.” Published in 1977 and one of his best-known novels translated into English, the book describes the comedic travails of Marito Varguitas, a young law student and aspiring writer who falls in love with his aunt against a backdrop of radio soap operas.

Ms. Urquidi responded to the book with a critical memoir of her time with Mr. Vargas Llosa, “What Varguitas Did Not Say,” detailing their threadbare and tension-filled years together in Europe. They divorced in 1964, and Mr. Vargas Llosa married Patricia Llosa, with whom he had three children.

They separated in 2015 after 50 years of marriage when he confirmed his romantic involvement with Isabel Preysler, the former wife of the singer Julio Iglesias. He and Ms. Preysler, who was born in the Philippines and became a high-profile socialite in Spain, separated in 2022.

He is survived by his sons Álvaro, a writer, and Gonzalo, a representative for the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, and a daughter, Morgana, a photographer.

Though deciphering Peru dominated much of his work, Mr. Vargas Llosa lived outside the country for long stretches. In the 1960s, in Paris, he worked as a translator and wrote news bulletins for Agence France-Presse to make ends meet, and later settled into a writing life in Barcelona before returning to Peru in the 1970s.

While Mr. Vargas Llosa gained greater fame as a novelist, his 1990 presidential campaign emerged as something of a surprise after he wrote an opinion essay denouncing President Alan García’s plan to nationalize banks.

As Peruvians grappled with hyperinflation, as well as a bombing campaign carried out by the Shining Path, a Maoist guerrilla group, Mr. Vargas Llosa temporarily stopped writing fiction and formed his own right-wing party, called Freedom Movement.

His cerebral candidacy, inspired by European and North American political and economic philosophers, and his very appearance, with his light-colored skin, trim physique and penchant for preppy sweaters, contrasted with an electorate largely made up of impoverished Quechua-speaking people and Spanish-speaking mestizos.

Mr. Fujimori, invoking his non-European ancestry, depicted himself as an ally of the lower classes long dominated by elite whites. Similarly, his opponents questioned whether Peru should be governed by Mr. Vargas Llosa after the writer acknowledged that he was agnostic.

Disillusioned by his failed foray into politics, Mr. Vargas Llosa left Peru again in the early 1990s, dividing his time between a writing base in London, where he had an apartment in Knightsbridge, and a home in Madrid.

To the dismay of many in Peru, King Juan Carlos of Spain signed a royal decree in 1993 granting Spanish citizenship to Mr. Vargas Llosa, who nevertheless kept a Peruvian passport and continued traveling to Lima.

In addition to the Nobel Prize, Mr. Vargas Llosa won other distinctions, including Spain’s Miguel de Cervantes Prize in 1994 and the Jerusalem Prize in 1995, and produced more than 50 novels, essays, plays and works of literary criticism throughout his long career.

Some of his best work examined the vagaries of history in Latin America, such as “The War of the End of the World” (1981), a mammoth fictionalized account of a late 19th-century messianic movement in Canudos, a town in the arid expanses of northeastern Brazil.

Mr. Vargas Llosa researched the book in the archives of Rio de Janeiro and Salvador, and finished writing it at the Wilson Center in Washington in 1980, not far from the battlefields of the Civil War, a conflict that may have helped him evoke the brutal violence with which Brazil’s aristocratic leaders crushed Canudos.

“I was enveloped by flying falcons and within viewing distance of the balcony where Abraham Lincoln spoke to his Union soldiers at the brink of the Battle of Manassas,” Mr. Vargas Llosa wrote in the book’s prologue.

Yet while he could write elegantly about anywhere, it was Peru that held for him a special fascination, mixed, he once wrote, with “suspicion, passion and rages,” even a hatred “steeped in tenderness.”

“You know that Herman Melville called Lima the strangest, saddest city,” Mr. Vargas Llosa, referring to a passage from “Moby Dick,” told an interviewer from The New York Times in 1989, when he seemed unable to detach himself from literature and introspection even in the heat of his campaign for president.

“Why?” Mr. Vargas Llosa said. “The fog and drizzle.”

Then he added, laughing, “I am not so sure that the fog and the drizzle are Lima’s big problems.”

Yan Zhuang and Elda Cantú contributed reporting.