It may not have been the tax-evasion trial of the century — the second century, that is — but it was of such gravity that the defendants faced charges of forgery, fiscal fraud and the sham sale of slaves. Tax dodging is as old as taxation itself, but these particular offenses were considered so serious under Roman law that penalties ranged from heavy fines and permanent exile to hard labor in the salt mines and, in the worst case, damnatio ad bestias, a public execution in which the condemned were devoured by wild animals.

The allegations are laid out in a papyrus that was discovered decades ago in the Judean desert but only recently analyzed; it contains the prosecutor’s prep sheet and the hastily drafted minutes from a judicial hearing. According to the ancient notes, the tax-evasion scheme involved the falsification of documents and the illicit sale and manumission, or freeing, of slaves — all to avoid paying duties in the far-flung Roman provinces of Judea and Arabia, a region roughly corresponding to present-day Israel and Jordan.

Both tax dodgers were men. One, named Gadalias, was the impoverished son of a notary with ties to the local administrative elite. Besides convictions for extortion and counterfeiting, his catalog of misdeeds included banditry, sedition and, on four occasions, failing to show up for jury duty at the court of the Roman governor. Gadalias’s partner in crime was a certain Saulos, his “friend and collaborator” and the supposed mastermind of the caper. Although the ethnicity of the accused is not explicitly stated, their Jewish identities are assumed, based on their biblical names, Gedaliah and Saul.

This ancient legal drama unfolded during the reign of Hadrian, after the emperor’s tour of the area around 130 A.D. and presumably before 132 A.D. That year, Simon bar Kochba, a messianic guerrilla chief, led a popular uprising — the third and final war between the Jewish people and the empire. The revolt was violently suppressed, with hundreds of thousands killed and most of the surviving Jewish population expelled from Judea, which Hadrian renamed Syria Palestina.

“The papyrus reflects the suspicion with which the Roman authorities viewed their Jewish subjects,” said Anna Dolganov, a historian of the Roman Empire with the Austrian Archaeological Institute, who deciphered the scroll. She noted that there is archaeological evidence for coordinated planning of the Bar Kochba revolt. “It is possible that tax evaders like Gadalias and Saulos, who were inclined to disrespect the Roman order, were involved in the preparations,” Dr. Dolganov said.

In the current issue of Tyche, a journal of antiquity published by the University of Vienna, Dr. Dolganov and three Austrian and Israeli colleagues present the court proceedings as a case study. Their paper brings to light how Roman institutions and imperial law could influence the administration of justice in a provincial setting where relatively few people were Roman citizens.

“The document provides rare and highly interesting evidence for the slave trade in this part of the empire,” said Dennis P. Kehoe, a classicist at Tulane University, who was not involved in the study, “as well as the circumstances under which Jews might have slaves.”

Following the papyrus trail

No one is certain when or by whom the papyrus was unearthed, but Dr. Dolganov said that it was probably found in the 1950s by Bedouin antiquity dealers. She suspects that the discovery site was Nahal Hever, a steep-walled canyon west of the deep cleft of the Dead Sea where some Bar Kochba rebels, fleeing the Romans, took refuge in natural fault line caves in the limestone cliffs. In 1960, archaeologists found documents from the era in one of the Jewish hide-outs; others have been discovered since.

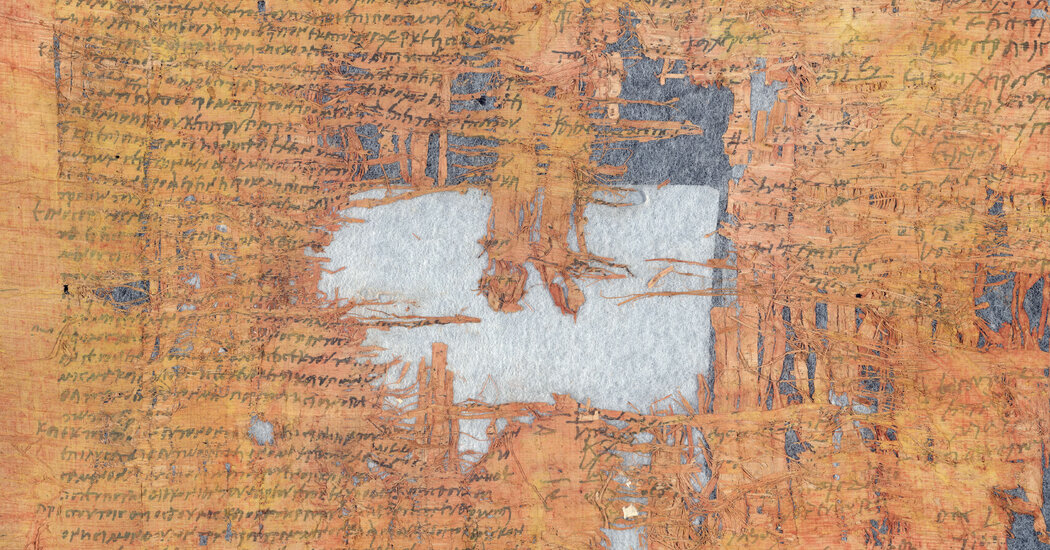

Initially misclassified, the ragged 133-line scroll lay unnoticed in the archives of the Israel Antiquities Authority until 2014, when Hannah Cotton Paltiel, a classicist at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, realized that it was written in ancient Greek. In light of the document’s complexity and extraordinary length, a team of scholars was assembled to conduct a detailed physical examination and cross-reference names and locations with other historical sources.

Deciphering the papyrus and reconstructing its intricate narrative posed major challenges to Dr. Dolganov. “The letters are tiny and densely packed, and the Greek is highly rhetorical and full of technical legal terms,” she said. Unlike in documents such as contracts, there were no formulaic expressions that made the translation easier. “It certainly does not help that we only have the second half, or less, of the original,” Dr. Dolganov said.

The researchers deduced that the tax scheme was designed to escape notice, which meant careful detective work was required to piece together what happened. “I had to adopt the perspective of the Roman fiscal administration to understand what the text is talking about,” she said. Dr. Dolganov also had to imagine the dodge from the standpoint of the accused: To commit tax fraud with the slave trade in the most remote corner of the Roman world, what would you have to do, and what would have made the effort profitable?

The ancient scheme has resonated deeply with modern tax lawyers. A German lawyer told Dr. Dolganov that the shenanigans of Gadalias and Saulos were not all that different from today’s most common forms of tax fraud — shifting assets, phony transactions. And the Roman interrogation methods were largely in line with Untersuchungshaft — investigative custody — for financial crimes, which involves intimidation and often brutal questioning.

“Dr. Dolganov has performed wonderful feats of scholarship in unraveling the meaning of the contents and their significance for the history of the region and the empire,” said Brent Shaw, a classicist at Princeton University with no connection to the project.

Rebels with a cause

The case against Gadalias and Saulos was bolstered by information provided by an informant who tipped off the Roman authorities — and the text even suggests that the informant was none other than Saulos, who denounced his accomplice Chaereas to protect himself in a looming financial investigation. The most likely scenario, Dr. Dolganov said, was that Saulos, a resident of Judea, arranged the bogus sale of several slaves to Chaereas, who lived in the neighboring province of Arabia.

By being sold across the provincial border, the slaves would have vanished in print from Saulos’s assets in Judea. But because they physically stayed with Saulos, the alleged buyer, Chaereas, could opt not to declare them in Arabia. “Thus, on paper, the slaves disappeared in Judea but never arrived in Arabia, thereby becoming invisible to Roman administrators,” Dr. Dolganov said. “Henceforth, all taxes on these slaves could be avoided.”

The empire had sophisticated systems for tracking slave ownership and collecting various taxes, which amounted to 4 percent on slave sales and 5 percent on manumissions. “To free a slave in the empire, you had to present documentary evidence of the slave’s current and previous ownership, which had to be officially registered,” Dr. Dolganov said. “If any documents were missing or looked suspicious, Roman administrators would investigate.”

To hide Saulos’s double-dealing, Gadalias, the notary’s son, evidently forged the bills of sale and other legal agreements. When the authorities became aware of the matter, the defendants allegedly made payments to a local city council for protection. At the trial, Gadalias blamed his late father for the forgeries, and Saulos pinned the manumission on Chaereas. The papyrus offers no insight into their motive. “Why the men took the risk of freeing a slave without valid papers remains a mystery,” Dr. Dolganov said.

One possibility is that, by faking the sale of slaves and then releasing them, Gadalias and Saulos were observing a Jewish biblical duty to free enslaved people. Or maybe there was profit to be made in capturing people — perhaps even willing participants — from beyond the border, bringing them into the Empire and then releasing them from their “slavery” to become free Romans. Or maybe Gadalias and Saulos were human traffickers, plain and simple — Dr. Dolganov emphasized that the alternate story lines were entirely speculative, as nothing in the text supported them.

What surprised her most about the trial, she said, was the professionalism of the prosecutors. They employed deft rhetorical strategies worthy of Cicero and Quintilian and displayed an excellent command of Roman legal terms and concepts in Greek. “This is the edge of the Roman Empire, and boom, we see legal practitioners of high caliber who are competent in Roman law,” Dr. Dolganov said.

The papyrus does not reveal the final verdict. “If the Roman judge was convinced these were hardened criminals and execution was in order, Gadalias as a member of his local civic elite may have received a more merciful death by decapitation,” Dr. Dolganov said. “At any rate, almost anything is better than being eaten by leopards.”